W. Jon Windsor, MLS(ASCP)CM

|

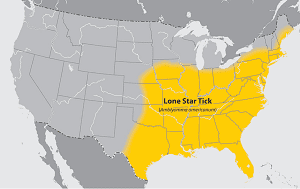

| Figure 1: A map of endemic areas (in yellow) for A. americanum |

Imagine all of your absolute favorite foods. Now, what if every time you enjoyed one of those foods, several hours later you were plagued with vomiting, stomach cramps, dizziness, and other symptoms closely resembling anaphylactic shock.1 This is the harsh reality of those unfortunate enough to consume meat of any kind after suffering a bite from the “Lone Star Tick” (Amblyomma americanum).

The lone star tick is notorious for biting humans and transmitting different pathogens known for causing diseases like tularemia, human echrlichiosis, heartland virus disease, and bourbon virus disease. However, a lesser-known condition a bite can leave behind is known as STARI (Southern tick-associated rash illness).2

What is STARI

A tick bite that leads to STARI results in a rash with a presentation similar to Lyme’s disease. Unfortunately, that rash is just the start. As the rash resolves, an allergy to galactose-a-1,3-galactose (a-gal) emerges.1

|

| Figure 2: The lone star tick has a characteristic white dot on its back |

A-gal is a carbohydrate found in the meat of several animals, excluding primates. A-gal is also found in the digestive lining of A. americanum. When we consume meat, a-gal becomes a great source for essential amino acid production. When the human body is exposed to a-gal through a tick bite, our immune system overreacts and mounts an allergic response with IgE antibodies.3

Very little research exists that has explored why this might occur. One theory is that the combination of lone star tick digestive proteins and a-gal mimic the “allergen epitope” that IgE antibodies readily bind to, which then identify a-gal as the “intruder” and elicits an immune response.4 What makes this under-researched phenomenon worse is that these lone star ticks are endemic to the Southeastern United States (Figure 1) with some high-risk areas going as far north as Maine.

According to the CDC, the times you are at the greatest risk for being bitten by A. americanum are between early spring and late fall. The way you can recognize this tick is by a characteristic white dot on its back (Figure 2).2

STARI is the precursor for the allergic response to meat, otherwise known as alpha-gal syndrome. Alpha gal syndrome is clinically diagnosed through a serious of questions asked by an allergist that seeks to gather information around the amount of meat you ate and the length of time after you consumed meat before symptoms started. A clinical diagnosis can be confirmed by both a skin IgE allergy test or by a blood test that measures the amount of IgE your body created in response to eating meat. The only way to “treat” alpha-gal syndrome is to avoid meat altogether. If anaphylaxis is a concern, allergists will prescribe an epi-pen.1

“[S]uch a ground-breaking discovery in the word of allergy medicine can only drive researchers forward in their pursuit to combat anaphylaxis and remove the burden allergens have on people across the world.”

Discovering the Link to the Lone Star Tick

The most compelling thing about alpha gal syndrome is the obscurity that surrounds an allergy to meat. An association between a-gal and the development of an allergy to meat was made through a rather unusual discovery. In 2008, an article was published that a small portion of individuals who were given the colorectal cancer drug “cetuximab” during a clinical trial were experiencing an allergic reaction. After further inquiry, the researchers were able to conclude that a-gal IgE antibodies already present within the subjects’ immune systems were inducing these allergic reactions to the treatment.

The subjects who were allergic to a-gal primarily resided in Tennessee, Arkansas, and North Carolina, which are all present within the lone star tick-endemic areas.5 Eventually, enough people with a-gal syndrome reported exposure to ticks. This drove researchers to look for a-gal in the digestive systems of ticks to establish a link. Just recently in 2018, a group of researchers were able to establish the presence of a-gal in the saliva and digestive tracts of lone star ticks.3

It’s exciting that we have identified how a meat allergy and alpha gal syndrome are linked to lone star tick bites. However, allergens and the allergic response are still poorly understood. Very few treatments exist that have successfully mitigated the allergic response. With that being said, such a groundbreaking discovery in the word of allergy medicine can only drive researchers forward in their pursuit to combat anaphylaxis and remove the burden allergens have on people across the world.

References

- Meat Allergy Overview. American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology Allergest. 2014.

- Shadick N MN, Hoak D. Tickborne Diseases of the United States a Reference Manual for Healthcare Providers. CDC. 2018.

- Chandrasekhar JL, Cox KM, Loo WM, Qiao H, Tung KS, Erickson LD. Cutaneous Exposure to Clinically Relevant Lone Star Ticks Promotes IgE Production and Hypersensitivity through CD4(+) T Cell- and MyD88-Dependent Pathways in Mice. J Immunol. 2019;203(4):813-824.

- Platts-Mills TA, Woodfolk JA. Allergens and their role in the allergic immune response. Immunol Rev. 2011;242(1):51-68.

- Chung CH, Mirakhur B, Chan E, et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1109-1117.

W. Jon Windsor is Foodborne Diseases Centers for Outbreak Response Enhancement (FoodCORE) aide at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment in Denver.