Beth Warning, MS, MLS(ASCP)CM, ASCLS Region IV Director

Congratulations! You may have just celebrated 40 years as a medical lab professional and are looking forward to retirement. You may be known as the coagulation guru, the “pee queen,” or the key operator for one of the analyzers. You remember running lithium testing on the flame photometer, adding caffeine to your bilirubin tubes, and performing RIA as a “new” technology. What does this mean?

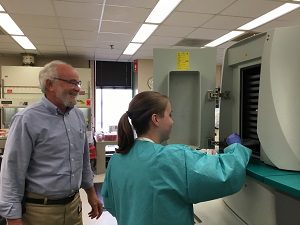

|

| It is vital that seasoned medical laboratory professionals share with our developing professionals the expertise that they maintain. Photo courtesy of Floyd Josephat. |

It means you have a long history in the profession and have witnessed many changes. You have experiential knowledge beyond any textbook. But how you use this knowledge is the key. As a seasoned tech, it is vital to share with our developing professionals the expertise that you maintain. In business, it may be called succession planning–in the lab, it requires transfer of the knowledge, skills, and level of practice to our next generation of laboratorians.

Recently, ASCLS leaders participated in a book club, reading Starts with Why, by Simon Sinek. While this book may have related to having great leadership to inspire marketing or management, as a scientist, I bet many of us started with why years ago. Your parents may have shared that “why” was your favorite or often-used word as a child. As scientists, we are challenged to ask this question in research. As educators, we hope to stimulate our students to both ask and answer the same “why” question.

So back to sharing your knowledge—often knowledge is not shared, the answer to “why” is not provided, and people move on, keeping information to themselves without realizing the benefit of continued learning.

“If we share our knowledge, answer the how and why questions in the field, our profession will be all the stronger.”

Knowledge Hoarders

There are names for these individuals who keep information as if it’s their own property. One is the knowledge hoarder. They see their expertise, job tasks, and skills as a form of job security, or even a form of power. The hoarder takes on new roles, learns new things, then keeps that knowledge to him or herself as a form of job security.

Knowledge hoarders may be some of the most frustrating people to work with. They may share what needs to be completed but are limited in the how to perform a task and completely avoid the why something should be done. Their resistance to sharing knowledge may stem from their fear of losing their advantage in the workplace. We need to quench the fear of losing status to keep their expertise within the organization.

Control Freaks

The knowledge hoarder is closely related to the control freak. Sure, we may be labeled as such as a laboratory professional, but in terms of knowledge sharing, this is the individual who has to know all the information. Then they can tell everyone how to perform a test, the best way (their way) to perform the test, and point out the mistakes and errors when something doesn’t go as planned. You know this person—they are the ones who think they know everything and give their advice freely without you actively seeking it.

While this person may not be sharing his or her expertise, they have strong opinions that their way is the only way and should be uniform across the lab. Knowledge sharing in this instance may need to be a two-way street, where the old adage of “leave your ego at the door” would apply.

Introverts

Some lab professionals may claim that they are not comfortable in training new employees or students. They hide by identifying as introverts, therefore keeping things close, not sharing much information in terms of work or workplace skills. It’s not something they are comfortable with, yet the expertise they display is irreplaceable in the workplace. There is a bridge that needs to be built, a mentorship or fostering of a relationship so that both individuals are comfortable in knowledge exchange.

Organizational Politics

Finally, there is always the political angle that prevents knowledge sharing—organizational politics, of course. This is where a person feels they are not adequately trained to teach, mentor, or even, not compensated for the role. This is an unfortunate position to be in, as our developing professionals and new employees are eager to learn and want to maintain or raise the bar on practice standards within the organization.

So how does this tie in with succession planning? Every lab needs to have a plan to capture and transfer this important knowledge. Through mentoring, the talents and skills of our retiring staff will be preserved and imparted to the next generation before retirement, in a structured format. Other options include documentation of processes and procedures by creating detailed process maps or SOPs for specific one-of-a-kind tasks. Job shadowing or retraining is another possibility.

In the laboratory, we are constantly challenged to learn new things—the test menu may be increased or decreased, analyzers come and go, and methodology changes. Add to this our large number of lab professionals reaching retirement age, and their knowledge is irreplaceable. Today’s workforce is more transient, moving from opportunity to opportunity, but if we share our knowledge, answer the how and why questions in the field, our profession will be all the stronger. Let’s promote succession planning and knowledge transfer for continuity of quality.

Beth Warning is assistant professor in the medical laboratory science program at the University of Cincinnati-College of Allied Health Sciences.