Volume 39 Number 2 | April 2025

Mahesh Percy, MBA, DMLT, ASCLS Today Volunteer Contributor

Ewarld Marshall, MD, MScMED, ASCLS Today Volunteer Contributor

Abstract

Malaria is a common parasitic infection in many tropical and subtropical areas, with Plasmodium vivax being one of the main species responsible. Typically, malaria is suspected in patients with fever who have traveled to areas where the disease is common. However, sometimes the parasite is found by accident during blood tests, especially when symptoms are unclear or unusual. In this case, we describe a patient who came in with a fever, but there was no clear cause for the illness. A routine blood test revealed Plasmodium vivax ring forms, confirming the patient had vivax malaria. This case highlights the need to consider malaria when diagnosing fever and the value of doing a blood smear test, even in places like Grenada, where malaria is not typically found.1

Introduction

Malaria remains a global public health concern, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions. Among the five Plasmodium species known to infect humans, Plasmodium vivax is second only to Plasmodium falciparum in prevalence and disease burden. Unlike P. falciparum, P. vivax is typically associated with milder forms of malaria but can still cause significant morbidity due to relapsing infections.2

The diagnosis of malaria relies heavily on the identification of parasites in the blood through microscopy, antigen detection, or molecular techniques. In cases where malaria is not initially suspected, the incidental discovery of Plasmodium trophozoites on a peripheral smear can lead to an unexpected but critical diagnosis, particularly in patients with non-specific symptoms like fever of unknown origin. This case report discusses an incidental finding of P. vivax ring forms and schizont forms during routine evaluation for fever in a patient with no initial suspicion of malaria.3

Case Presentation

A 22-year-old male presented to the clinic with complaints of intermittent fever, malaise, and body aches over the past week. The fever was described as cyclical, occurring predominantly in the evening, with associated chills and sweating, but no accompanying headache, nausea, or vomiting. The patient denied any recent travel to malaria-endemic areas, outdoor camping, or exposure to known vectors such as mosquitoes. He also reported no significant past medical history, including no previous episodes of malaria.

The initial physical examination revealed a mildly febrile state (38.2°C), with no other abnormal findings on systemic examination. There was no pallor, jaundice, or hepatosplenomegaly. The patient’s respiratory, cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal systems were unremarkable.

A basic panel of laboratory investigations, including complete blood count (CBC), liver function tests, CRP, ESR, and renal function tests, was ordered. The CBC revealed mild leukopenia (WBC count of 4,300/μL) and borderline anemia (hemoglobin of 12.5 g/dL). No leukocytosis or other abnormalities were noted. Given the presence of fever with mild leukopenia, a peripheral blood smear was requested for further evaluation.

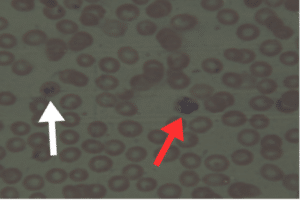

To their surprise, the peripheral blood smear showed the presence of Plasmodium vivax ring forms and schizont forms (Figure 1), confirming a diagnosis of vivax malaria. The smear revealed classic features of P. vivax, including enlarged, pale erythrocytes and the presence of Schuffner’s dots in the infected red blood cells.4

Figure 1. White arrow ring form and red arrow Schizont form

Upon further questioning, the patient recalled that several months ago he had traveled to a rural area known to have intermittent malaria outbreaks. Although he had not been acutely ill during or immediately following the trip, this prompted the suspicion that the malaria had been contracted during that time and had manifested in a delayed, low-grade form.5

Discussion

The diagnosis of malaria, particularly in non-endemic regions or in patients without a travel history, can be challenging. Fever is a non-specific symptom, and clinicians may not always consider malaria as a primary diagnosis unless there is an obvious history of exposure. In this case, the incidental finding of P. vivax ring forms on a peripheral smear was unexpected, as the patient’s initial presentation did not strongly suggest malaria.

P. vivax is known for its ability to cause relapsing infections due to dormant liver-stage hypnozoites, which can activate weeks or months after the initial infection. This phenomenon explains why patients, like the one in this case, may present with malaria long after leaving an endemic area. The cyclical nature of fever in P. vivax infection is also characteristic but may be mistaken for other febrile illnesses, particularly in regions where malaria is not endemic or when patients do not recall recent exposure.6

The use of peripheral smear microscopy remains the gold standard for diagnosing malaria. Despite advances in molecular diagnostics, peripheral smear examinations offer the advantage of detecting not only the presence of the parasite but also specific morphological features that help differentiate between Plasmodium species. In this case, the detection of P. vivax ring forms and schizont forms was critical for both diagnosis and management, allowing for prompt initiation of antimalarial therapy.

This case underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for malaria in patients with fever, even in the absence of classic risk factors, such as recent travel to endemic areas. The fact that P. vivax can lie dormant for extended periods emphasizes the need for clinicians to consider remote travel histories and to utilize routine diagnostic tools like peripheral smears when investigating unexplained fever.7

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of routine peripheral blood smear examinations in the workup of fever, especially when initial diagnostic efforts fail to identify a cause. The incidental discovery of Plasmodium vivax ring forms and schizont forms in this patient underscores the value of considering malaria, even in cases where the clinical presentation is not immediately suggestive. P. vivax remains a significant cause of relapsing malaria, and this case serves as a reminder of its diagnostic importance for timely intervention. Early detection and treatment of malaria are crucial for reducing morbidity and preventing potential complications, especially in non-endemic regions where the diagnosis may be easily overlooked.8

References

- White NJ. Plasmodium knowlesi: the fifth human malaria parasite. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(2):172-173. doi:10.1086/524889

- WHO Global Malaria Programme. World Malaria Report 2022. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

- Price RN, Tjitra E, Guerra CA, Yeung S, White NJ, Anstey NM. Vivax malaria: neglected and not benign. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77(6 Suppl):79-87. PMID: 18165478.

- Mueller I, Galinski MR, Baird JK, Carlton JM, Kochar DK, Alonso PL, et al. Key gaps in the knowledge of Plasmodium vivax, a neglected human malaria parasite. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(9):555-66. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70177-X.

- Baird JK. Evidence and implications of mortality associated with acute Plasmodium vivax malaria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(1):36-57. doi:10.1128/CMR.00074-12.

- Anstey NM, Russell B, Yeo TW, Price RN. The pathophysiology of vivax malaria. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25(5):220-227. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2009.02.003.

- Howes RE, Battle KE, Mendis KN, Smith DL, Cibulskis RE, Baird JK, Hay SI. Global epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95(6 Suppl):15-34. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0141.

- Zimmerman PA. Plasmodium vivax infection in Duffy-negative people in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(3):636-638.

Mahesh Percy is Medical Technologist/Instructor at St. George’s University in St. George’s, in Granada.

Dr. Ewarld Marshall is Chair of Pathology and is the Medical Pathology Laboratory Director at St. George’s University in St. George’s, in Granada.