Volume 35 Number 3 | June 2021

Kora Freeman and Izabel Hanson

Introduction

Introduction

Capnocytophaga canimorsus is a bacterial human pathogen with serious clinical implications. C. canimorsus is known to infect hosts with underlying health conditions and is considered normal flora in felines and canines. The organism is a thin gram-negative rod which can appear small on the Gram stain (see Figure 1), ranging from 1-3 micrometers long. The organism is capnophilic and normally requires 48 hours or more to become visible in culture. Notable rapid testing includes positive test results for both oxidase and catalase. Additionally, C. canimorsus is non-spore forming and non-motile. In humans, the organism can present as a localized infection, often at the site of a dog or cat bite, but it can enter the bloodstream and cause septicemia (Mahon 2015).

Purpose of Case Study

This case study aims to educate readers on the organism of Capnocytophaga canimorsus by utilizing a real-world example. C. canimorsus is a fastidious organism that does not grow well in culture due to its capnophilic atmosphere requirements. Patients with compromised immune systems, underlying health issues, and splenectomies are more susceptible to being infected by this organism, and they may suffer serious health problems such as septic shock and disseminating intravascular coagulation (DIC) (Mahon 2015).

As described in this case study, the organism may often be overlooked as the cause of infection, which can lead to poor patient care. Because the organism was identified by an experienced microbiologist, this patient received intravenous antibiotics and did not suffer any lasting issues from the infection. Educating the medical laboratory community on the key clues for suspicion of C. canimorsus and proper isolation techniques may help save lives and improve patient care.

Case Summary

A 59-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to a physician’s clinic after suffering a bite from his pet dog on his left ankle. The bite left an open wound on the man’s ankle that appeared red, swollen, and blistered. A wound swab (eSwab) was collected for culture. No medication was prescribed at this time. The wound swab was cultured on both aerobic and anaerobic media. The aerobic wound culture isolated many normal skin flora on Chocolate Agar (CHOC) and Sheep’s Blood Agar (BAP) only. No organisms grew on MacConkey (MAC) Agar. The anaerobic wound culture was finalized at five days with no growth. A final culture report identified only normal skin flora.

Two days after the dog bite, the man presented to the emergency room (ER) with a fever, joint pain, body aches, and loss of appetite. A complete blood count (CBC) and two sets of blood cultures were collected and sent to the clinical laboratory. The initial CBC showed no critical values, nor a heightened white blood cell (WBC) count. The two aerobic blood culture bottles flagged positive at 24 hours after incubation. Both anaerobic blood culture bottles were reported as no growth at five days.

The positive blood culture bottle Gram stains showed thin gram-negative rods, slightly curved on the ends. Both aerobic bottles were inoculated to agar media including CHOC, BAP, and MAC, then incubated in CO2. The medical laboratory scientist (MLS) decided to also inoculate a Campylobacter (CAMPY) Agar plate based on the Gram stain morphology. After 24 hours of incubation the culture had no growth on any of the agar media. The plates were re-incubated overnight, but still appeared as no growth at 48 hours.

The MLS assigned to the culture became concerned because the positive blood culture Gram stain showed there was some sort of aerobic organism present in the blood culture, but nothing was recovered in subculture. Initially, the MLS attempted to incubate plates in anaerobic conditions in the hopes that she could get the organism to grow. She consulted other microbiologists in the laboratory and decided to examine the CHOC plate under a specialized dissecting microscope designed for magnifying colony growth on culture media.

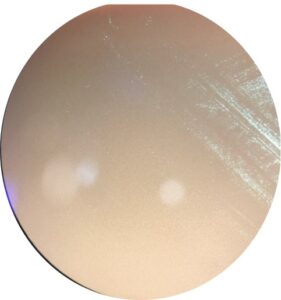

Under the microscope there were small, white, glistening colonies that were barely visible (See Figure 2). The colonies were analyzed by matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) and identified as Capnocytophaga canimorsus. The instrument used for the identification was not validated for this organism, so unfortunately C. canimorsus could not be reported to the physician. The culture was sent to a reference laboratory for complete identification and susceptibility testing, though it is known that C. caninmorsus is routinely susceptible to penicillin antibiotics (Verghese et al., 1988).

It was later discovered that the patient received Ertapenem intravenously, which is a carbapenem class antibiotic. The infection presented as secondary bacteremia and did not develop into sepsis with serious complications because of immediate antibiotic intervention. Common signs and symptoms of a C. caninmorsus infection include fever, gastrointestinal issues, headache, and fatigue. Serious complications from this infection may include disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and septic shock (Janda et al., 2006).

Conclusion

Capnocytophaga canimorsus is an opportunistic pathogen that can cause sepsis following a dog bite. The capnophilic organism is difficult to isolate and identify in culture without proper incubation conditions and identification techniques. This case study was a classic example of how C. canimorsus can cause a serious infection in immunocompromised individuals.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, October 16). Capnocytophaga. https://www.cdc.gov/capnocytophaga/transmission/index.html

- Janda, J. M., Graves, M. H., Lindquist, D., & Probert, W. S. (2006). Diagnosing Capnocytophaga canimorsus infections. Emerging infectious diseases, 12(2), 340–342. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1202.050783

- Mahon, C. R., Lehman, D. C., & Manuselis, G. (2015). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology (5th edition). Saunders

- Verghese, A., Hamati, F., Berk, S., Franzus, B., Berk, S., & Smith, J. K. (1988). Susceptibility of dysgonic fermenter 2 to antimicrobial agents in vitro. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 32(1), 78–80. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.32.1.78

Kora Freeman and Izabel Hanson are Medical Laboratory Science Students at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, Nebraska.

Figure 1: Capnocytophaga canimorsus Gram Stain

Figure 2: Culture Growth Seen Under Dissecting Microscope

BAP Plate: macroscopic

BAP Plate: microscopic

CHOC Plate: macroscopic

CHOC Plate: microscopic