Zac Lunak, PhD, MLS(ASCP)CM, HTL(ASCP)

|

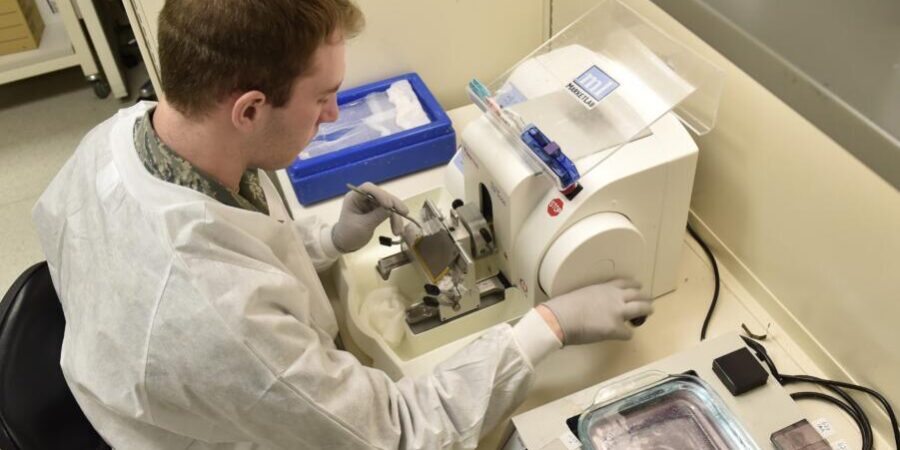

| A histotechnician embeds patient tissue into a mold. Photo credit: Ilka Cole |

|

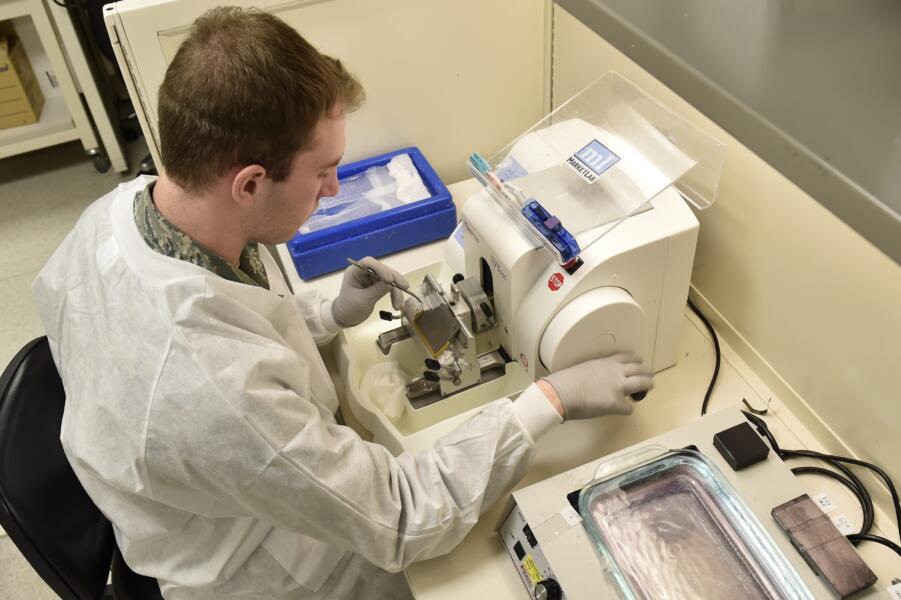

| A histotechnician uses a microtome to cut samples of patient tissue. Photo credit: Tech Sgt. Liliana Moreno |

As medical laboratory professionals, many of us probably work, or have worked, in close proximity to a histology (pathology) lab. You may have wondered, what exactly happens within a histology lab and who works there? I worked as a medical laboratory scientist (MLS) for several years and was unable to answer this question with any clarity or confidence. It was not until I completed a histology program and was certified as a histotechnologist (HTL) that I truly understood and appreciated the field.

This article will introduce the histotechnology profession by describing the general tasks of an HTL or histotechnician (HT) and briefly touch on the current issues within the profession. My goal is to build on the collaboration between the histotechnology and medical laboratory fields, and perhaps initiate a relationship between the histology and medical laboratories within your workplace.

Duties of a Histotechnologist and Histotechnician

Tissues that are analyzed in the pathology lab can range anywhere from large surgical specimens to small biopsies only millimeters in length. Either way, every specimen needs to immediately be placed in a fixative, which is most often a formalin solution. Fixation preserves the architecture of the components within the tissue and is essential for optimal analysis.

Upon specimens entering the laboratory they are assigned an accession number, much like an MLS laboratory specimen. Initially, the specimen is examined and described macroscopically by a trained professional, most often a pathologist or pathologist assistant (this is referred to as grossing). Larger samples are cut into smaller pieces (about the size of a coin) and placed into tissue cassettes for microscopic preparation. At this point, the HTL/HT typically takes over and completes four main tasks: processing, embedding, microtomy, and staining.

Processing involves ultimately removing the water from the fixed tissue and having it infiltrated with a wax which makes it easier to cut in thin slices. To do so, the tissue is moved through a series of chemical solutions. This step is largely automated, but the HTL/HT is responsible for setting the different incubation times, ensuring the chemical solutions are rotated and filled properly, as well as several other maintenance responsibilities.

Once the tissue is processed, the HTL/HT removes them from the cassette and embeds the tissue. At this step, the tissue is placed in a mold, completely filled with a warm wax (liquid form). The wax used most often is paraffin and is the same wax used to infiltrate the specimen during the last step of processing. During this embedding step, it is crucial for HTL/HTs to orient the specimen correctly in the mold. Incorrect orientation will make it difficult or impossible for the pathologist to determine a diagnosis/result.

Once the specimen is properly oriented, the mold is immediately cooled. Consequently, the wax hardens which forms a nice foundation around the tissue making it easier to cut. The excess wax is removed, and the resulting tissue block is then ready for microtomy. The blocks are placed within a specialized tissue slicer, called a microtome. Trained HTL/HTs roughly cut into the tissue and make sure all areas of the tissue are exposed before cutting thinner slices for analysis. Once the tissue has been faced enough, the HTL/HT cuts the tissue at the recommended depth (usually 4 μm), and a ribbon is formed between each slice. The ribbon is placed in a water bath to decompress and then it is placed on a slide. Slides are then allowed to dry and are ready for staining.

Almost every tissue that goes through the histology lab will have a routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain performed on it. The hematoxylin will stain the nuclei blue whereas the eosin will stain the cytoplasm pink. Other tissue structures will stain different hues of the eosin, making them able to be differentiated as well. The H&E stain provides a nice way to analyze the architecture and layout of the cells within the tissue and usually enables the pathologist to answer the questions he or she needs to make a diagnosis. However, sometimes more testing is needed.

Most histology labs contain several “special stains” to help the pathologist confirm a particular diagnosis. For example, one of the more common special stains performed is a trichrome stain, which can help differentiate between smooth muscle and collagen and helps detect cirrhosis. Some special stains can detect microorganisms like fungi or bacteria. In fact, a Gram stain is one of the special stains that can be performed on fixed tissue. In total, an HTL/HT is trained to understand and troubleshoot up to 50 different special stains.

“[Histology] truly is a good mix of hands-on work, automation, and a lot of troubleshooting. The field is often referred to as both an art and a science.”

Discussion

This article does not do the histology profession justice by any means, but hopefully you have a better understanding of what an HTL/HT does on a day-to-day basis. It truly is a good mix of hands-on work, automation, and a lot of troubleshooting. The field is often referred to as both an art and a science.

To become an HTL/HT, one can become certified as a histotechnologist (HTL) or a histotechnician (HT). The HTL, similar to the MLS, would be the four-year degree; the HT, similar to the MLT, would be the two-year degree. Certification through ASCP can be obtained either by going through a National Accrediting Agency for Clinical Laboratory Sciences (NAACLS)-accredited program or one year of on-the-job training with the proper amount of academic background.

Staff-shortages, lack of recognition, licensure … sound familiar? The issues within the histology lab are pretty much identical to the medical laboratory field. Vacancy rates are increasing and are currently at about 8.5 percent.1 Licensure and required certification remain a struggle within the histology profession. Currently, only four states have licensure requirements for HTL/HTs. There are several other states that are trying to get licensure approval.2

Given the similarities of their professional issues, it only makes sense for histology and medical laboratory fields to collaborate. In 2018, the National Society of Histotechnology (NSH) joined ASCLS and several other lab organizations at the annual Legislative Symposium for the first time. This is a great way to initiate a stronger relationship between these two fields and organizations. Hopefully this can initiate collaboration at the state and local levels. I encourage ASCLS leaders to reach out to their nearby NSH state and regional chapters.2 Most importantly, in your workplace, don’t be afraid to simply stop by the histology lab and say hello.

References

- Garcia E, et al. The American Society of Clinical Pathology’s 2018 Vacancy Survey of Medical Laboratories in the United States; American Journal of Clinical Pathology 2019; 152(2): pp 155-168

- National Society of Histotechnology

Zac Lunak is assistant professor, medical laboratory science, at the University of North Dakota School of Medicine & Health Sciences in Grand Forks.